By Chalsey Dooley Some days seem magical—things go well, I try some new ideas, I have something to show for the hours I’ve spent at various tasks. Then there are other times when I get to the end of the day struggling to find something of note that I accomplished. Sure, the kids were fed and dressed, they did their home-learning activities, they played in the park … but I still feel I want more. I want to be able to check off several things from my long to-do list. I want to be able to say I made leaps of progress. But rather than that, I feel like I’m falling further behind in so many areas of life. At the end of a long day a few months back, I was trying to push off the weight of despondency from having so much to take care of, with problems piling up faster than I could keep up with. Then I walked into the bathroom and found Patrick (two years old) had taken his soft, fuzzy, stuffed platypus, filled up the sink, given it a good wash, and now had poured baking soda (which I use for cleaning the sink) all over it. I didn’t need more messes to clean up. But it did look kinda cute, so I chuckled to myself, thinking,Even though I can’t seem to get around to any of my other goals, at least the platypus is clean! Later, as I looked at the children, happy, cozy in bed, waiting for their bedtime story, I decided to change my criteria for “accomplishment” and a “good day.” Now I go down a new list and see how many “checks” I can put. § Did I help my children smile today? § Was I patient when things didn’t go smoothly? § Did I show each son that I loved him personally? § Was I available to help, listen, and encourage, even at the cost of not “getting something done”? § Did I pray for someone today? § Did I laugh and choose to take things in stride when I felt like I was being pushed over the edge? Tomorrow’s another day. Eventually the to-do list will work out. Plod. Breathe. Smile. Plod. Breathe. Smile. We’ll get there, eventually, wherever “there” is actually meant to be. Chalsey Dooley is a writer of inspirational material for children and caregivers and is a full-time edu-mom living in Australia. Check out her website atwww.nurture-inspire-teach.com. Article originally published in Activated magazine. Used with permission. Photo by Kate Henderson via Flickr

0 Comments

William J. Bennett, excerpted from The Educated Child Nothing stirs stronger passions among educators—or parents and policymakers—than the issue of how children should be taught to read. Which is better for your child, phonics, or the “whole language” approach? In phonics, children begin by learning the basic sounds represented by letters and combinations of letters; they are then taught to “decode” written words by “sounding them out,” letter by letter and combination by combination (e.g., the difference between the and a).Phonics teachers usually emphasize the single accurate spelling of any word. Lessons often include games, drills, and skill sheets that help youngsters associate the letters with sounds. Students read “decodable” stories containing only words they can sound out using the phonics lessons they’ve learned. Whole language teachers, on the other hand, generally take the view that phonics drills and stories with phonetically controlled vocabulary turn students off. They hold that children acquire reading skills naturally, much the way they learn to speak. In their view, understanding the relationships between sounds and letters is only one of many ways students can learn to recognize new words, and sound-letter relationships do not necessarily need to be formally taught. Whole language theory says that children learn to read and write best by being immersed in interesting literature, where they learn words in a context they enjoy and understand. Students are encouraged to figure out the meaning of new words using a variety of cues, such as by associating them with accompanying pictures, or looking at the ways they are used in sentences along with more familiar words. The argument between phonics and whole language advocates has been raging for decades. (“I have seen the devastating effects of whole language instruction on older students,” a Colorado teacher writes, for example. “These students cannot spell or write properly because of years of learning bad habits encouraged by whole language.”) It’s come to be known by some as the “Reading Wars.” Yet many years of experience as well as research by scholars such as Jeanne Chall, Marilyn Adams, and Sandra Stotsky tell us that there really should be no debate at all. The evidence is clear: an effective reading program combines explicit phonics instruction with an immersion in high-quality, interesting reading materials. This is an important topic, so we want to be clear. Most children get off to a better start learning to read with early, systematic phonics instruction. Therefore, the teaching of these skills should be a vital part of beginning reading programs for most youngsters, and should be in the instructional kit of every primary school teacher. If your child’s teacher doesn’t believe in using—or does not know how to use—phonics instruction as part of reading class, your child may have trouble learning to read proficiently. Whole language proponents, however, do make a good point. Schools should also offer children intriguing books and wonderful stories. The love of reading, after all, arises not from mastery of decoding techniques but from being able to apply those newly acquired methods to engaging material. Phonics exercises are necessary to help most young children master the letter sounds, but drills and worksheets are not enough. They do nothing to capture the child’s imagination as literature can. All readers, even the youngest, should be given entertaining stories geared to their level. In this respect, a healthy blend of phonics and whole language makes the most sense. The best primary teachers make phonics a fundamental part of their classrooms, but have at their disposal a whole arsenal of other techniques—and plenty of terrific reading materials. They use both interesting decodable texts and great children’s literature containing vocabulary that is not phonetically controlled. Some phonics advocates are so enthusiastic that you might erroneously get the impression that phonics is supposed to remain part of English class throughout one’s education. As an explicit part of reading instruction, however, it is something to be taken up very seriously in the earliest years; for most children, it gradually fades into the background by the end of third grade. Learning phonics should be like learning to balance on a bicycle—at first it takes lots of conscious practice, but once mastered is virtually effortless. You want the act of decoding words to become automatic as quickly as possible, freeing your child to focus on meaning and the pleasure of reading. How do you know if your child’s teacher is paying the right amount of attention to phonics in the earliest grades? Simply put the question to her: Do you teach phonics? If she responds, “No, we don’t stress that,” you may very well have a problem. You need to find out exactly what her instructional philosophy is, and what kind of track record it has. Even if she nods and says, “Yes, we teach phonics,” it does not tell you how effective a job she’ll do. Outrageous though it is, some primary school teachers have a shaky grip on effective methods of teaching reading. This is rarely because they’re stupid or uncaring, but rather because they’ve passed through a teacher training program or college of education that didn’t do the job properly, or where the professors frown upon the whole notion of phonics. (“I was told by the ‘professionals’ that they didn’t teach phonics because ‘English is not a phonetic language,’” one disconcerted mom reports.) Furthermore, hearing a teacher say “We teach phonics” does not tell you how much phonics she puts into the mix, or how it’s done. On the one hand, it may mean so much work with thebah, bob, bih, boh, buh sounds that reading turns into a dreary chore. On the other extreme, there are some schools that throw a few token sound-letter games into the lesson plans just so parents will feel assured that their children are “learning phonics.” Schools have discovered that most parents “believe in” phonics—but sometimes teachers are perfunctory about it. The best strategy is to keep an eye on your child’s progress when the school begins to teach reading, whether in kindergarten or first grade. Take a good look at the materials and assignments. Visit the class one day and observe a reading session. Is there an emphasis on making sure children learn the connections between letters and sounds, through drills, worksheets, word games, questions from the teachers, and entertaining stories that children read? Even more important, though, is to sit down with your beginning reader on a routine basis to see how and what he’s reading. If he can read more words this week than the week before, if he tries to sound out new words, and if he seems to enjoy spending time with his books, the balance is probably right.

Text adapted from Wikihow. Photo by Gerry Thomasen via Flickr.

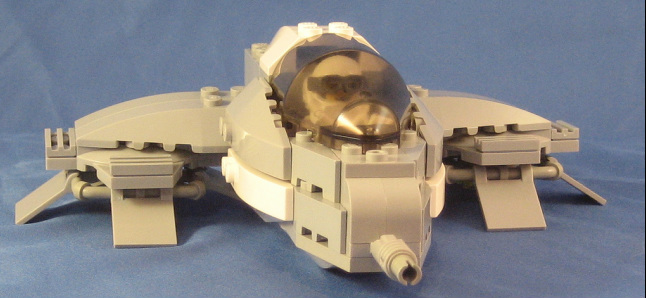

Flor Cordoba My four-year-old son, Ricardo, is “on the Lego trip.” Maybe it’s his age or the fact that he’s artistic and loves building things, but not a single day goes by that I don’t find him building something with his Lego. Sometimes I sit with him and build too. I am quite impressed with his cars, spaceships, and whatnot, so I put up with the fact that I have to go hunting around the house for tiny missing pieces almost every day. One day he came running to show me a new spaceship he had built, and accidentally bumped it against a doorway. The hapless little spaceship was thrown into what seemed a thousand pieces that went everywhere—across the floor and under the table, chairs, couches, and every other hard-to-get-at place in the room. Ricardo’s face registered total dismay. I tried to comfort him. “It’s okay. Now you can build another one and I’m sure it will be even better. Don’t get discouraged. Just pick up the pieces and build a new one.” But poor Ricardo was so downcast that he said he wasn’t going to try again. He slowly picked up the pieces and went to put them away. A few minutes later, he came bounding back with a brand-new spaceship. “You were right, Mom,” he said. “This is way better than the last one!” I was so proud of my little boy, and it taught me a lesson. How many times have I worked to build a dream, only to have it fall to pieces! Picking up the pieces and starting over is often even harder than getting started the first time, but with the faith of a little child, all things—even better things—are possible. Article courtesy of Motivated magazine. Used with permission. Photo by Mark Anderson via Flickr.

A six-year-old came home from school one day with a note from his teacher in which it was suggested that he be taken out of school as he was “too stupid to learn”. His name: Thomas Alva Edison. *** If you have a boy who just can’t learn in your class, don’t despair. He may be a late bloomer. It has now come out that Dr. Wernher von Braun, the missile and satellite expert, flunked math and physics in his early teens. *** A boy who was so slow to learn to talk that his parents thought him abnormal & his teachers called him a “misfit”. His classmates avoided him and seldom invited him to play with them. He failed his first college entrance exam at a college in Zurich, Switzerland. A year later he tried again. In time he became world famous as a scientist. His name: Albert Einstein. *** A young English boy was called “Carrot Top” by other students & given “little chance of success” by some teachers. He ranked third lowest in class: grade averages for English was 95%, history 85%, mathematics 50%, Latin 30%. His teacher’s report reads: “The boy is certainly no scholar and has repeated his grade twice. He has also a stubborn streak and is sometimes rebellious in nature. He seems to have little or no understanding of his school work, except in a most mechanical way. At times, he seems almost perverse in his ability to learn. He has not made the most of his opportunities.” Later, the lad settled down to serious study and soon the world began to hear about Winston Churchill. Compilation courtesy of TFI. Photo by Sasvasta Chatterjee via Flickr.

The Parents Zone, Web Reprint, adapted Generation means all human beings born and living around the same time; also known as coevals. When there is a significant gap of time between two coevals, it is defined as “generation gap.” When we compare two generations and when there is a considerable difference in the lifestyles, habits, likes, and dislikes of the people belonging to these two separate times, problems due to age gap arise. It is no secret that this gap is widening rapidly. More and more parents and their offspring agree that they just can’t understand each other. This lack of understanding of social, moral, political, musical, or religious opinions leads to lack of acceptance, which is one of the primary reasons why families break. Here are a few tips for parents to help bridge this ever-widening gap: 1. Communicate constantly. It is simply a fact that communication plays an important role in bridging gaps between not only parents and children, but also in every relationship that we can think of. When we communicate respectfully with our children, we are letting them know that we are willing to do all it takes to lessen the age gap and understand things from their point of view. 2. Be open minded. Open mindedness means widening our horizons. When we widen our horizons and we open the doors and windows of our heart, we look at things with a new perspective. This helps us understand why what is being said is actually said. This is very important if we want to understand our children’s priorities and habits. 3. Learn to accept. Trying to understand our children’s world is no mean task. It takes a lot of effort to understand the younger generation. We have to accept first that we lived in a different world. For us, that was an ideal world, with less corruption, hypocrisy, cheating, and every bad thing we see so much increased now. Then, we will have to accept today’s times too, especially the fact that not everything is that bad, and make the effort to understand and accept our children’s perspectives and priorities. That is a big step towards bridging the generation gap. 4. Listen and understand. We as parents sometimes tend to talk too idealistic. We will have to stop that, and we will have to learn to listen, and then to understand. Giving lectures is not at all a good idea. 5. Silence is golden sometimes. Yes, sometimes we have to learn to be silent too. We have to let our children voice their opinions and listen to what they are saying, without interrupting them. In conclusion, the reality of a generation gap is only in terms of age. If we set our egos aside and look at things from an entirely different perspective, we can minimize the gap between our children and us. This does not mean we should not do what we need to do as parents. It just means we become a little more understanding and accepting of what our children see as “their world.” Courtesy of Motivated magazine. Used with permission.

Linda and Richard Eyre, Teaching Children Joy Adults often bristle when someone remarks that they are “just like so-and-so.” We like to think of ourselves as unique, different, and one-of-a-kind, which is how it is meant to be. It is good to remember that there is much more to what makes a person a unique individual than, for example, the obvious characteristics of a person’s astrological sign, their interests, the number of children they have, or the type of clothes that they wear. In a similar fashion, parents should learn to appreciate the uniqueness that each child brings to their lives. Each child needs to feel special and important in his or her own right. Seeing each child as an individual with varying likes and dislikes, will help to make the child feel loved for who he is and is meant to be. Here are some tips on how we can encourage our children’s unique qualities and characteristics:

Ponder: Take time to reflect on each of your children’s qualities and strengths. Make a list of these qualities and focus on encouraging and praising your children for them. Text courtesy of Motivated magazine. Used with permission. Photo by Patrick via Flickr.

Perseverance pays Young people can drive you up the wall at times! But keep trying to reach them and relate to them. Try to get on their level and be one with them. If you can develop a link, a connection, then you can start getting through to them and making some real progress. Frustration is the price you have to pay when you work with young people. That’s just the way it sometimes is; that’s just a fact of life. Your knowledge and experience comes from years of ups and downs, successes and failures, and quite a few trying situations, whereas these teens are just starting out. Keeping that in mind will help you to have patience. Also, try not to compare this group with other teens you have worked with; some kids are slow at wanting to grow up, others are quicker. You can’t let yourself get overly frustrated about these things. Let them break the mold As young people grow up, they generally need more freedom to make their own choices without someone trying to fit them into a certain mold. Some people just don’t and won’t fit into the mold you try to put them into! You’ve got your mold, you’ve got your idea about how they should be or act, but you can’t expect even your children to be that way, to be just like you and totally conform to your ideals. You may need to start changing your perspective. You may need to change the way you look at these young people, and start looking for things that you admire about them—for how well they do in spite of the pressures and difficulties they face. Be willing to get your hands dirty Don’t give up! Just get in there and don’t worry about getting your hands dirty. It is a bit like gardening—you can’t really be a gardener unless you are willing to get your hands dirty. Plants aren’t going to thrive or grow if all the gardener is willing to do is just watch them and water them. Sometimes plants need re-potting because their roots are getting too long and numerous for the pot they’re in, or the soil they are in needs to be changed because it has lost its nutrients or is getting moldy. So it is with growing young people—they may need some personal attention from someone who isn’t afraid to get right in there and help them find solutions to their problems. Sometimes they get tangled up and just can’t help themselves, and they need the help of the gardener. Watch out for them like the gardener watches out for the warning signs—leaves turning yellow or getting spotted or drying up, soil getting moldy or plants drooping from insufficient water. There are shade plants, and there are sun plants; there are plants that need a lot of water, and there are others that hardly need any. There are plants that need much care and have to be misted daily. Then there are cacti that hardly need any care. Your part is to just be a faithful, loving, caring gardener—to keep your eye on those plants and do what you can to help tend and care for them. The gardener learns what he can do, and does what he can to help the plants. And like any gardener, you can only give it your best, then you must leave the rest up to God. Excerpted from “Parenteening”, by Derek and Michelle Brookes. © Aurora Productions. Photo by Kristin via Flickr.

|

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

LinksFree Children's Stories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed