|

By Iris Richard I was born in 1955, only ten years after World War II, when wartime hardships were still fresh in people's minds. Grandfather used to tell us children of the extreme hunger and exhaustion of those days, and the struggle of staying alive during the long freezing winter months. Our town was in the heart of Germany's industrial center, and everything was covered with a seemingly permanent layer of gray-brown dust from the steel mills. In springtime, the grass and green shoots quickly turned brown, and so did the fresh snow in winter, making its white coat look worn after only a day. On the first Sunday in December, our family always gathered around the table in our apartment's tiny kitchen. My mother, my sister Petra, and I lit the first candle of our Advent wreath and sang Christmas songs, as our thoughts journeyed far, far away from the dusty city to the three wise men traveling on camelback. Each week a new candle was lit, and peace and joy filled our hearts as the story of the manger which awaited the birth of our Savior came alive. Then came the long-awaited event of Christmas baking—special indeed, since butter, nuts, and eggs were sparse, and chocolate was a rare treat. With the delicious smell of freshly baked cookies still filling the air, we carefully stored each batch in large tin cans. On Christmas morning, we went to see the tree, prepared the night before by our parents. We all crept into the living room while Papa lit the candles one by one with a long match. What joy it was to find stockings filled with homemade cookies, nuts, chocolate, oranges, and apples, and new knitted dresses for our dolls. There also were crayons and coloring books, hats, gloves, and scarves. These were days of simple joys and handmade toys. The memories serve as a reminder to me to search for true value, for the human touch, for things that last—especially in the fast-moving times we live in today, filled with technological gadgets and screen-based activities. They are also a reminder to keep my eyes open to the needs of others, to love, and to share. That's what makes this season a truly unforgettable one, leaving its beautiful mark on the memories of our children and those we meet. Iris Richard is a counselor in Kenya, where she has been active in community and volunteer work since 1995. Article courtesy of Activated magazine; used with permission. Photo by Celeste Lindell via Flickr.

0 Comments

Web Reprint, www.kidshealth.org, excerpts Depression isn’t just bad moods and occasional melancholy. It’s not just feeling down or sad, either. These feelings are normal in kids, especially during the teen years. Even when major disappointments and setbacks make people feel sad and angry, the negative feelings usually lessen with time. But when a depressive state, or mood, lingers for a long time—weeks, months, or even longer—and limits a person’s ability to function normally, it can be diagnosed as depression. Recognizing Depression If you think your child has symptoms of depression, it’s important to take action. Talk with your child and your doctor, or others who know your child well. Many parents dismiss their concerns, thinking they’ll go away, or avoid acting because they may feel guilty or prefer to solve family problems privately. For a long time, it was commonly believed that children did not get depressed and that teenagers all went through a period of “storm and stress,” so many kids and teens went untreated for depression. Now more is known about childhood depression, and experts say it’s important to get kids help as soon as a problem is noticed. Parents often feel responsible for things going on with their kids, but parents don’t cause depression. However, it is true that parental separation, illness, death, or other separation can cause short-term problems for kids, and sometimes can trigger a problem with longer-term depression. This means that if your family is going through something stressful it’s usually helpful to turn to a counselor, therapist, or other expert for support. It’s also important to remind your child that you’re there for support. Say this over and over again—kids with depression need to hear it a lot because sometimes they feel unworthy of love and attention. Remember, kids who are depressed may see the world very negatively because their experiences are shaped by their depression. They might act like they don’t want help or might not even know what they are really experiencing. Getting help for your child Your first consultation should be with your child’s pediatrician, who probably will perform a complete examination to rule out physical illness. If depression is suspected, the doctor may refer you to a specialist who can diagnose and is qualified to treat depression. These health professionals can help, but it is important that your child feels comfortable with the person. If it’s not a good fit, find another. Your child’s teacher, guidance counselor, or school psychologist also might be able to help. These professionals have your child’s welfare at heart and all information shared with them during therapy is kept confidential. What can I do to help? Most parents think that it’s their job to ensure the happiness of their kids. When your child’s depressed, you may feel guilty because you can’t cheer him or her up. You also may think that your child is suffering because of something you did or didn’t do. This is not necessarily true. If you’re struggling with guilt, frustration, or anger, consider counseling for yourself. In the end, this can only help both you and your child. Other ways to help:

Depression can be frightening and frustrating for your child, you, and your entire family. With professional advice and your help, your child can start to feel better and go on to enjoy the teen and adult years. Courtesy of Motivated! magazine. Used with permission.

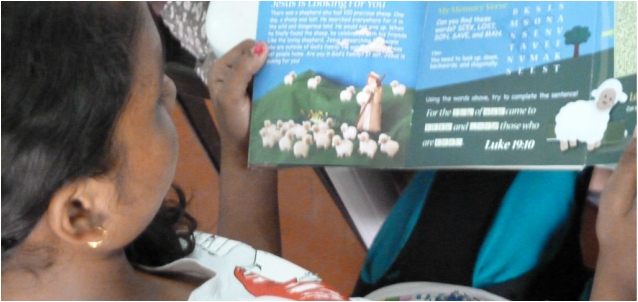

Parables of Jesus for Children – Free Stories, Videos, Coloring Pages and Activity Sheets11/16/2014 When Jesus spoke to the multitudes, He often explained deep truths by means of parables—stories about common events, circumstances, and things that His listeners could easily relate to. Times have changed, but the timeless truths contained in the parables of Jesus are just as relevant today and just as feeding to our souls as they were to those who first heard them 2,000 years ago! Bon appétit! Stories:

Videos: Short videos (for children up to 5 years in age)

Full length cartoons (about ½ hour; ideal for children ages 5 – 10)

Activities and Coloring Pages

Worksheets for older children:

Image courtesy of FN-Goa via Flickr.

Disabilities cover a wide range. Some are obvious—such as a child with a physical disability who uses a wheelchair, or a child with a visual impairment who uses a cane to navigate when walking. Other disabilities may be more “hidden”—for example, children who have learning disabilities or autism spectrum disorder. Chances are that at some point your child will have a classmate with a disability. Just as you guided your very young child when he or she began to befriend others, you can encourage your child to learn about and be a friend to children who have special needs. Basic ideas to share with your child

Try to use clear, respectful language when talking about someone with special needs. For a younger child, keep explanations simple, such as, “She uses a wheelchair because a part of her body does not work so well.” Reinforce with your child that namecalling— even if meant as a joke—is always unacceptable as it hurts people’s feelings. Getting to know children with special needs Paradoxically, when it comes to approaching someone with a disability, children may be better at it than their parents because they are less inhibited. Some adults—especially those without previous exposure to people with special needs—may be more timid. Worried about appearing intrusive or insensitive, they may not know what to say or do. “The other kids are great,” [Jasmine’s] mom says, “They are very direct, which is good. They like her and want to interact with her.” However, if your child (or you, for that matter) is unsure about approaching a child with a disability, here are some helpful tips:

Learning more about special needs Reading or learning about a disability is a great way to further understand a child’s experiences. It may also help dispel any questions you or your child may have. Your local library and librarian can be a great resource for finding age-appropriate books and materials. Deborah Elbaum, M.D. is a parent of three children and lives in Massachusetts. She is a volunteer for the disability awareness program taught at her children’s school. Article courtesy of Motivated magazine. Used with permission. Photo in public domain.

Dr. Bob Pedrick "Daddy, where does the light come from?" Billy had just switched on the lamp by his bed. Now he looked at his father with wide, questioning eyes. The question was a serious one for a seven-year-old. His father answered by describing in simple terms how the bright light of the sun pulls the water from the ocean into the sky. It then falls as rain in the mountains. He went on to describe the giant water wheels that capture the power of rushing water and change it into invisible streams of electric energy. This energy passes swiftly through miles and miles of wire until it reaches the light bulb, which, almost magically, can turn the invisible power back into light. After a few more questions, Billy's eyes lit up and his face broke out in an "I see" kind of smile. A choice moment had arrived, more awesome than the miracle of electricity. A portion of knowledge from the father's head had been transferred to Billy's brain. When we, as parents, send verbal messages that are received and assimilated by our children, it makes each of us glow a little. We could call this happy phenomenon turning on the light bulb inside our child's head. Unfortunately, the circuits for this kind of communication have a way of getting short-circuited. The father could have heard the question as another attempt by Billy to delay his bedtime. A response such as "No more silly questions. You've been up too long already" would have quickly blanked out the circuit and snipped off a promising tendril of inquiry into the unknown. More important, it would have broken another connection for real communication between child and parent. Of course, the same question in another context might well have been only manipulative on the part of the child, but the difference can be discovered by an alert adult. One key ingredient in this light bulb dialogue was that Billy wanted to hear what his father had to say. While this is characteristic of early childhood—when parents are the source of most knowledge and children absorb new ideas like a blotter soaks up water—this openness to parental input seems to lessen with each passing year. Instead of our parental wisdom lighting a bulb inside our children's heads, it seems as if their ears are plugged with wool. What we say bounces off, seemingly unheard. We wait in vain for any positive reaction. Finding a formula for popping the wool out of our children's ears gives promise of appreciably reducing the tension in many households. The practice of responding to family situations with verbal attacks upon the worth of the other person is an easy trap to fall into. It is so easy to tell other people how to avoid falling into this adversary message trap. Right now I was brought up short. While writing this, my granddaughter burst into my study. "Gramps," she shouted, "come see the dog jump three feet in the air for a bone." My first inclination was to snap, "Can't you see I'm busy? Don't bother me now." Then, before the words left my mouth, the subject of this chapter hit me. I thought, If you can't practice it, don't write it. Jeannie and I spent ten happy minutes watching our aged dog act like a puppy again in exuberant response to the loving attention of a six-year-old. My first inclination to respond by saying, "Can't you see I'm busy?" would have been an adversary message, starting with "you" and implying that if Jeannie were half-bright, she would have had better sense than to interrupt me. This was not at all the message I wanted to send. In this instance it was possible and productive for me to take a ten-minute break and play with Jeannie and the dog. This is not always the case; sometimes circumstances prevent a positive response to a child's request. In such an instance, I could have said, "Jeannie, I must finish this job right now. We will have to wait until later to put the dog through her paces." Jeannie would have been disappointed, but she probably would have received it as an affirmative message rather than an adversary message. It would not have insulted Jeannie's self-worth at all but, instead, let her know my needs. Note that this affirmative message began with "I," not with "you." The emphasis is placed upon the sender's situation and needs, not the character or intelligence of the receiver. The needs of parents are important, so affirmative messages are a useful means of popping the wool from children's ears. In contrast, I remember some years ago when a situation with a far higher emotional threshold occurred at our dinner table. Jeff, like a lot of kids, insisted upon setting his milk on the edge of the table. Repeated warnings that he should move his milk to a safe position failed to do more than cause a temporary correction. We were in a hurry; I had a speaking engagement that evening. Of course, the inevitable happened: Jeff reached for the bread, and milk spilled all over the new carpet. My roar was probably heard two blocks away. All of the tension from a long, trying day was focused upon Jeff. He left the table in tears. "You clumsy idiot!" I shouted after him. "Why don't you listen when I tell you something?" A look around the table told me no one else had much appetite for finishing the dinner. In one way I felt better, because the outburst had released the tightness I had unconsciously been building up. Still, I felt guilty.—Guilty for venting my anger by overreacting to Jeff's indiscretion. And guilty for spoiling the family dinner. No amount of self-reassurance that I had been justified in correcting Jeff's carelessness could relieve my depression. Later, before he went to bed, I put my arm around Jeff and we talked about the episode. Then we were able to give respectful attention to each other's feelings. An exchange of "I'm sorry" and a good hug made the end much better than the beginning. In the years since Jeff was small enough to disrupt the dinner table, I have become fully convinced that there are inevitably destructive results to be expected from using adversary messages. They tear at a child's dignity. Unquestionably, Jeff needed to be corrected that evening. His thoughtless and disobedient behavior was unacceptable, and I would have done him a disservice by ignoring it. A better response would have been, "I am really furious; milk on the carpet makes an ugly stain and causes us a lot of unnecessary work." Then Jeff should have been given an opportunity to help clean up the mess. Haim Ginott's remarks on this subject, while they are directed at teachers, are just as applicable to parents: "An enlightened teacher is not afraid of his anger, because he has learned to express it without doing damage. He has mastered the secret of expressing anger without insult. Even under provocation he does not call children abusive names. He does not attack their character or offend their personality." An idea internalized by a child when he receives a parental correction is not always the same idea the parent wanted to get across. Often the emotion-packed insult wrapped around a message is received and believed. The child misses the parental intent completely. We, as parents, then say that the child might as well have his ears stuffed with wool for all he hears. This is not precisely true, for the insult ("You are a stupid slob!") is heard, while the message we want delivered ("This behavior is unacceptable.") is sidetracked. Words Count When words fail between parent and child, the youngsters are set adrift in a void with no tools at their disposal to express ideas and needs. The importance of using and not abusing language was recognized by the Biblical author James. He was deeply concerned about relationships between persons, and he laid great emphasis upon being genuine. For example, his advice was to be "doers of the Word, and not hearers only" (James 1:22). On the subject of communication he said, "Be quick to hear, slow to speak, slow to anger" (James 1:19). In these few words he summed up the whole idea of this chapter. James started by giving a plug for effective listening. Then he cautioned against speech before thought. His proverb was an older, more profound version of the popular quip, "Put your mind in gear before you open your mouth." It is good advice, especially for parents when tension builds and frustrations mount. Excerpted from the book "The Confident Parent" by Dr. Bob Pedrick.

By Becky Hayes I had been praying for my son, Denith, to develop a close and personal relationship with Jesus while he was young, capitalizing on how much faith and capacity to believe two-year-olds have. I prayed that he wouldn't only come to know Jesus as his Savior, but also as the close and personal Friend that Jesus desires to be to everyone. I wanted Denith to sense His Spirit and to hear His voice. One night something very special happened that encouraged me and made me determined to teach my son more about how to hear from Jesus on his own. Denith had received a teddy bear when he was a baby, affectionately named "Teddy," and he was very attached to his stuffed friend. Everywhere Denith went—to preschool, to lunch, or to the supermarket—Teddy came along. One day Teddy was misplaced and could not be found. For three days we searched the house. I pulled everything out from under the bed in case he had fallen behind the bed and gotten stuck. The third night that Teddy was lost, I was putting my nine-month-old, Leilani, and Denith to sleep. The lights were out, and the children were all tucked into bed and ready to pray for the night, when Denith asked, "Mommy, where's Teddy?" "Honey," I said, "Teddy's lost. We need to look for Teddy during the day when there's light. Right now it's dark and we can't see. But why don't we ask Jesus to give Teddy a good night, and to help him be warm and cozy and sleep well." "Mommy, where's Jesus?" asked Denith. "Jesus is in your heart," I replied. "He's also in my heart, and He's all around us. If you talk to Him, He can hear you speak, and if you listen, you can hear Him talk to you." Without any further questions Denith promptly asked aloud, "Jesus, where's Teddy?" A short pause followed, and then in an excited but matter-of-fact manner, Denith exclaimed, "Oh, Mommy, Teddy is in the crib!" My body tingled with excitement. I knew that my son had heard Jesus answer his question. I didn't hesitate for a second. I began removing the toys and stuffed animals from the baby's crib. Sure enough, under the other toys, I saw Teddy. I was so touched by Jesus' love for Denith in rewarding his faith by answering him so clearly. It was also a good opportunity for me to show Denith that Jesus always has the answers. Courtesy of Activated! magazine. Used with permission. Photo adapted from Wikimedia Commons.

|

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

LinksFree Children's Stories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed